Treating more than just a symptom

Treating more than

just a symptom

Moody College professors share hopes for the future of aphasia patients through their work

When actor Bruce Willis’ aphasia diagnosis was made public in the spring of 2022, searches for the term spiked. Since then, aphasia has been increasingly on the public’s radar as more celebrities, including talk show host Wendy Williams, have come forward with diagnoses.

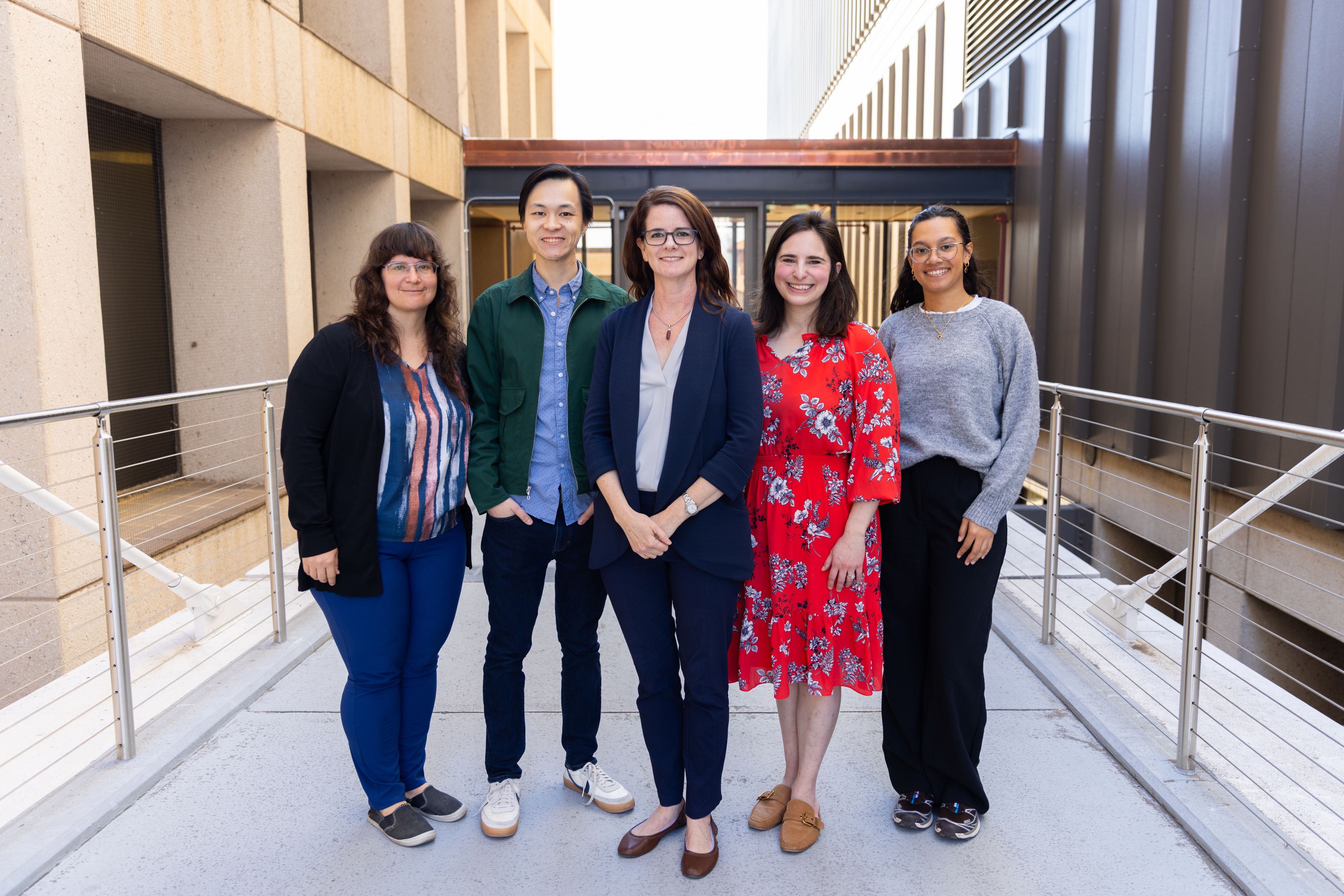

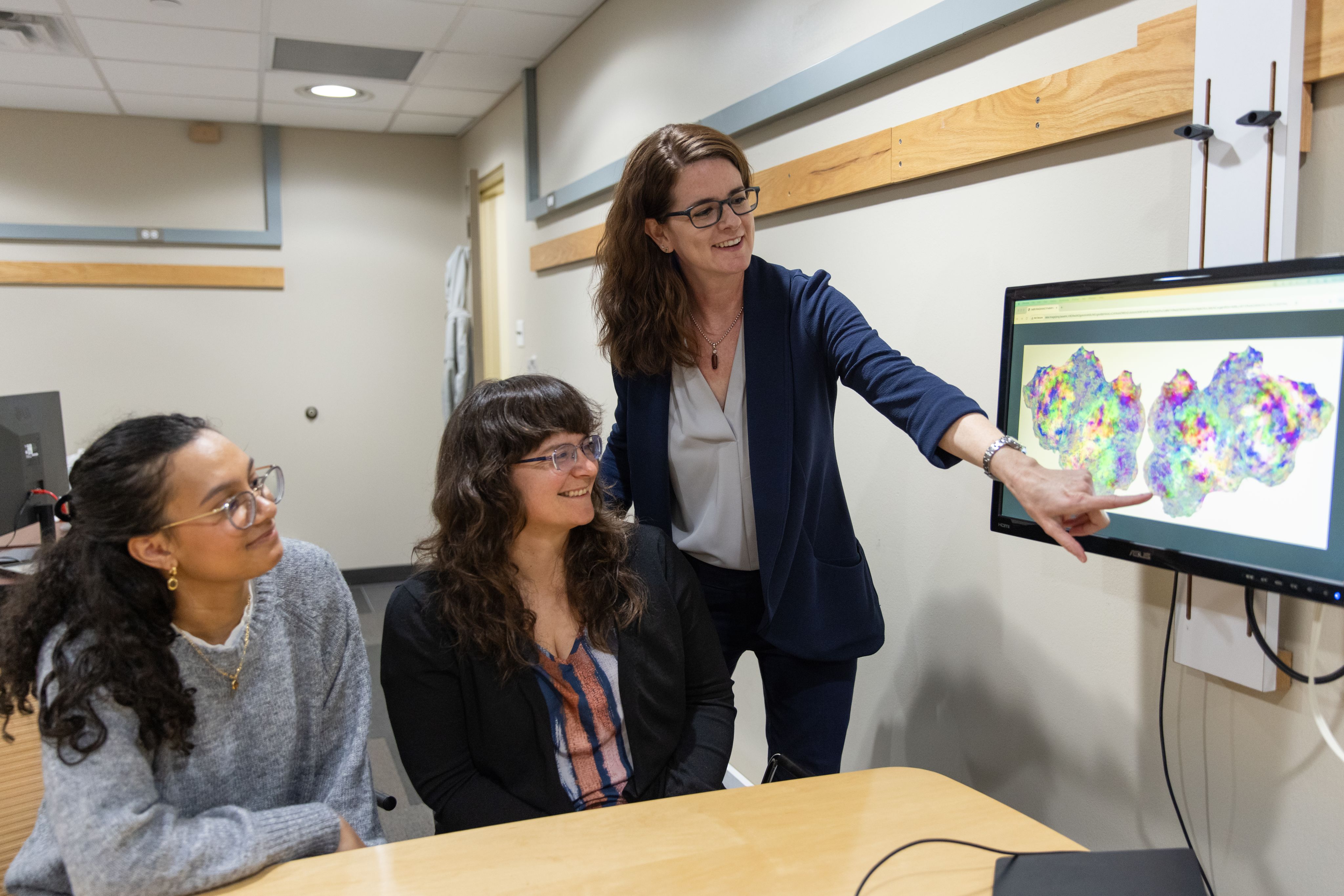

Despite media buzz, Maya Henry, an associate professor in Moody College of Communication’s Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, says there’s still so much to learn about the disorder and an array of misconceptions to dispel.

“I remember when Bruce Willis’ family first came out with his aphasia diagnosis,” Henry said. “The word was all over the news, but it was being referred to as a disease. Aphasia is like a headache. It’s a symptom of something going wrong with your brain. It’s not a disease.”

Aphasia is an acquired impairment of language caused by damage to the brain. It commonly occurs after a stroke or brain injury, causing people to lose the ability to produce or comprehend words.

In the Aphasia Research and Treatment Lab, Henry focuses on primary progressive aphasia, or PPA — a type of aphasia that causes gradual changes in language.

“It’s caused by neurodegenerative disease, so it’s actually a kind of dementia.” Henry said. “With Alzheimer’s dementia, which everybody’s pretty familiar with, people lose their cognitive abilities in the domains of memory and other cognitive functions. In progressive aphasia, other aspects of thinking and interacting with the world are spared, but people are losing their ability to communicate.”

Progressive aphasia, which is a type of frontotemporal dementia, can manifest in different ways. People may have trouble finding words, even ones they frequently use, or can drop connecting words in sentences, making their speech less precise and more difficult to understand.

Photo by Campbell Williams

Photo by Campbell Williams

Because this type of aphasia may affect people who are as young as their 50s or 60s, these changes are often written off as a normal byproduct of age or just everyday forgetfulness, which can lead to misdiagnosis in the early stages.

“It feels really subtle in the beginning, and people start thinking ‘Oh I’m stressed out, I’m tired, I’m depressed,’” Henry said. “And they’re told by their physicians in many cases that they just need to eat and sleep better and remove stress from their life.”

Progressive aphasia, Henry says, is always devastating. The diagnosis promises that from this day forward, communication is going to get harder and harder until patients are rendered mute and eventually pass away from other complications of neurodegenerative disease.

“With Alzheimer’s dementia, which everybody’s pretty familiar with, people lose their cognitive abilities in the domains of memory and other cognitive functions. In progressive aphasia, other aspects of thinking and interacting with the world are spared, but people are losing their ability to communicate.”

Stephanie Grasso, an assistant professor in the Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences who studies progressive aphasia in bilingual individuals, says the loss of language can be especially harrowing because many patients still have children at home or are still working.

“It’s such a hard thing to wrap your mind around when all you’re having difficulty with is saying a few sounds and really complex words or not being able to find a word once in a while,” Grasso said. “Planning for that trajectory is just an impossible thing.”

Stephanie Grasso, an assistant professor in the Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences, studies progressive aphasia in bilingual individuals. Photo by Lizzie Chen

Stephanie Grasso, an assistant professor in the Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences, studies progressive aphasia in bilingual individuals. Photo by Lizzie Chen

There’s still a relative lack of information about primary progressive aphasia. While there is a genetic component and known risk factors, there is an imperfect and limited understanding of why certain people develop it.

“Much like with Alzheimer’s disease, which has been studied in depth for a very, very long time, we still don’t have a very granular understanding of what sets all of this into motion and what causes these proteins to start folding incorrectly in the brain which causes cell tissue death,” Grasso said.

Although there is still no cure for progressive aphasia in sight, Henry says they’ve made headway from the “clinical nihilism” she saw in the early 2000s, where patients were rarely referred to therapy.

Various drug trials are underway in labs across the country, as well as an increasing number of behavioral interventions. Henry’s lab has conducted National Institutes of Health-funded clinical trials studying restitutive treatments that give patients strategies to find words and speak more fluently. Henry is also working on arming people with other means of communication: writing, gesturing, drawing or using apps.

“We also know that communication is a two-way street,” Henry said. “It’s not just the person with aphasia who bears the responsibility of successful communication. It’s the communication partner or partners. We think it’s super important to intervene with spouses, kids and family members.”

Henry believes it's crucial to think about the whole person when designing treatment — not just the disorder. This plays into her search for counseling and support groups made specifically to support patients with aphasia and their loved ones.

“We also know that communication is a two-way street.”

There are a number of avenues for treatment options Henry hopes to explore more in the future. From using non-invasive brain stimulation to change the way neurons are firing to decoding concepts from people’s brain activity using MRI scanners and AI.

“There’s so much potential to leverage technology to provide people with increasingly sophisticated tools for rehabilitation, but also to make rehabilitation really fun,” Henry said. “Right now, a lot of what we give people to do is very repetitive and kind of boring, and there’s no reason why we can’t have ultra realistic avatars who are helping us with treatment. Why can’t we sort of gamify things and make it motivating to engage with different kinds of treatment?”

Henry and Grasso both hope that more people with progressive aphasia begin to feel seen in the health care industry and get diagnosed earlier and more accurately.

“Part of what we try to help them think about, and part of what we’re studying, is how to help these people to maximize their communication and maintain what they’ve got for as long as possible,” Henry said. “It’s not just about giving people hope, but it’s about establishing an evidence base to show that there are a lot of things that we can do to help these folks.”

Henry and Grasso’s research is made possible by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Those interested can learn more about the bilingual aphasia project here.