Beyond the Facts

Beyond the Facts

Science Communication minor helps Moody students tell today's most pressing stories

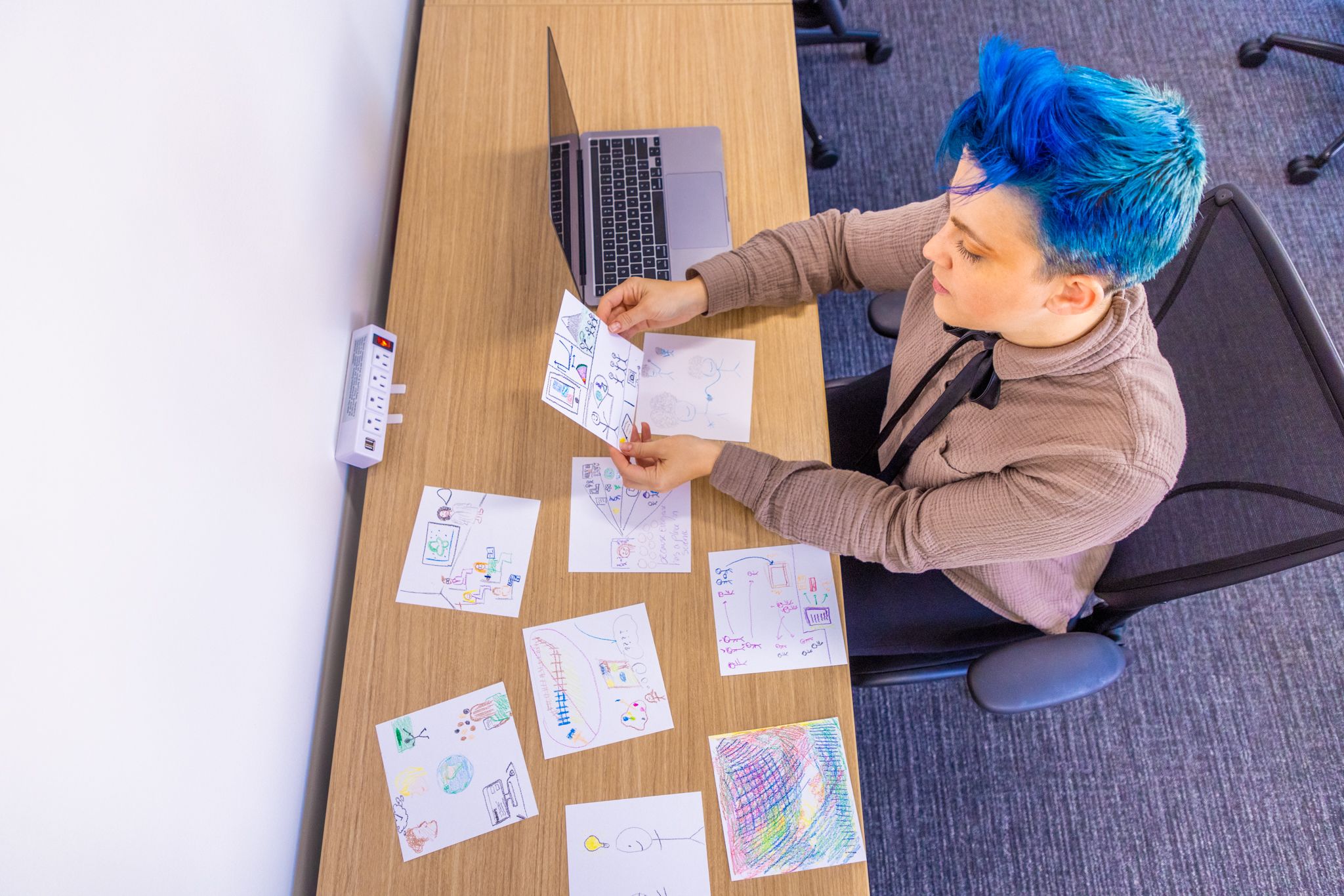

River Terrell came to The University of Texas at Austin in 2019 with a plan to go to medical school. But after nearly three years of taking premed courses, they realized they enjoyed writing papers and doing presentations about science more than actually being in the lab doing scientific research.

“I was the one in my family that people would ask, ‘How does COVID work?’ and I would get on my white board and explain viruses and vaccines,” they said.

On a whim, Terrell decided to take the Public Communication of Science and Technology course at the Moody College of Communication. They were so moved by the class that they reached out to their teacher Anthony Dudo, an associate professor in the Stan Richards School of Advertising & Public Relations, to see if he had any opportunities for undergraduate researchers.

Today, Terrell studies how journalists and scientists interact, their similarities and their differences and how they can communicate more effectively.

“We are more similar than we like to think,” they said. “Both scientists and journalists are very concerned with the accuracy of what they put out, being reputable and checking facts."

Terrell will graduate next year with a degree in biology from the College of Natural Sciences and a minor in science communication. But rather than continuing with med school, they’ve decided to get a master’s degree from Moody College.

“The science communication space is really expanding, and today we’re redefining how we think about science,” they said. “It’s not just boring facts from a lab. It matters, and it has a lot of implications for social justice and human rights, medical racism, health equity, impacts with LGBTQIA+ individuals, all of those intersect.”

"The science communication space is really expanding. It's not just boring facts from a lab. It matters, and it has a lot of implications for social justice and human rights."

Terrell is one of 32 students right now seeking a minor in science communication, which is available to both Moody College and College of Natural Sciences undergrads and requires 18 hours of coursework in topics such interviewing, advocacy, environmental reporting and creatively communicating scientific research.

Moody College Dean Jay Bernhardt started the minor in 2016 with the College of Natural Sciences after seeing the need for more effective communication about science and scientific research, something that can be difficult because of the complexity of topics, whether it be nanotechnology or neuroscience, and the difficulty putting them in laymen’s terms in a way that’s accessible for a general audience.

Today, Dudo, who is faculty chair of the minor, emphasizes the need for science communication that extends beyond simply conveying scientific information accurately to general audiences. Through his research and teaching, he seeks to help scientists become more sophisticated in how they think about and approach science communication, encouraging them to talk to organizations and audiences in ways that demonstrate care, shared values and the human side of science.

After graduating with a degree in communication, Dudo’s first job was in marketing for a natural history museum, where his work intersected daily with scientists.

“I was the person who was supposed to translate and tell stories about all the amazing things the scientists were doing with the public,” Dudo said. “Some of the scientists were very media savvy and understood why they needed a media department and others didn’t. I thought this was a problem. You guys are doing really important work but don’t know how to communicate about it or the value of communicating about it.”

It was not long after that Dudo shifted his entire career to focus on the study and practice of science communication, helping people in STEM fields share with the public about their work so that people can be informed and make better choices, about how to treat the environment, support their health and all the issues that scientific discovery supports.

"Good communication is not the same as communication. They are different. Effective communication takes time, expertise, money, effort and evaluation."

Today, Dudo said his Public Communication of Science and Technology course typically has as many as 200 students, which includes not just advertising and public relations majors but also chemistry, biology, neuroscience and more.

And it’s growing in popularity, he said, perhaps because science communication is more important than ever. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, climate change, life-threatening viruses, these issues have risen to the public conscience. However, they aren’t easy topics to talk about and understand, while they have an enormous effect on sustaining a healthy future.

At the same time, effective science communication has become more complicated by the proliferation of mis- and disinformation online, some of it nefarious but much of it accidental, because scientists don’t know how to talk to journalists, and journalists don’t know how to ask the right questions about science.

Dudo and others in the field are trying to change that.

“Public health, pandemics, climate change, energy, earthquakes, all of the things we read about on a daily basis have science at the center of them,” said Lee Ann Kahlor, a professor in the Stan Richards School of Advertising & Public Relations who researches science communication and teaches a course on the psychology of advertising. “We really need communicators and storytellers who can grapple with science and tell stories that help lead to a public understanding of science.”

Kahlor, who is also editor in chief of the academic journal "Science Communication," said that telling stories about science requires simplifying the language we use so that people don’t need a college degree to enjoy the story. It also means not being afraid to ask scientists what may seem like dumb questions and not shying away from courses with the word “science” in them, just because they seem intimidating as a communications major.

“Sometimes I feel like students see the word science and they cringe,” Kahlor said. “But these aren’t science classes. The courses in the minor teach students to tell stories about science, and there are so many interesting stories to tell.”

Kahlor’s research looks specifically at how and why people seek out information about science, health and other risk topics like climate change, which she has found says more about social pressure and belonging more than intellectual curiosity.

Kahlor has found that when we think others are informed about scientific issues, or expect us to be, we are more likely to seek out knowledge on those issues.

“What’s more interesting,” Kahlor said, “is that these social norms work with avoidance too. If I expect that the people I care about are actively avoiding a topic, I will want to avoid it, too."

This phenomenon is becoming especially common today as people become overwhelmed by fanaticism, political contention and news about crises they feel they can do little to solve on their own, such as climate change.

“I think scholars are really stressed right now about the proliferation of misinformation and people selecting ignorance in the face of facts that should be informing their behavior,” Kahlor said. “We worry and wonder what we can do differently to engage people. Honestly we are still figuring that out. What I can recommend is that we start thinking about people as social creatures who are negotiating more than any one particular crisis.”

“Talking about things cognitively versus experiencing it with your body are very different. So much of communication is not about words.”

While science communication is more critical than ever, it’s often not reflected in today’s newsrooms and scientific organizations. The shrinking budgets of traditional news media organizations mean there are hardly any full-time science reporters anymore. Most are freelance journalists, and they don’t get paid well for what they do. On the research side, very little investment is invested in communication efforts. Many scientists still consider communication a “soft skill,” and not as important as investing in things like lab equipment.

“Communication is often devalued,” said Nichole Bennett, an advertising and public relations Ph.D. student. “We really have to think about changing that going forward.”

“Effective communication takes time, expertise, money, effort, evaluation,” Dudo added. “The model for science communication for a long time has been serendipity, the opposite of scientific theory."

Bennett, too, came to UT Austin with a science background, looking to study biology, after a childhood spent fascinated with marine biology and butterflies.

Bennett found scientific research very isolating and research labs not always a place of belonging. “STEM spaces don’t always feel welcoming to people who don’t fit the stereotypical scientist’s norm,” they said.

Today, Bennett melds science and theater to help bring humanity to the STEM fields and encourage scientists to feel more present in their bodies and connected to each other.

“Talking about things cognitively versus experiencing it with your body are very different,” they said. “So much communication is not about words.”

Dudo hopes to grow the minor in the coming years to put additional emphasis on strategic communication. Good science communication is about more than translating scientific jargon and telling good stories, he said. There is a tremendous need to look at whether the communication being done helps the scientific community achieve its goals.

“That second level connection is often missing,” Dudo said. “We inform and assume something good is going to happen. There is no effort to assess the impact of communication and if it is actually moving behavior. Scientists need to think about the behavior they want to happen and then tailor their communication to achieve that.”