Cutting through the noise

Cutting through the noise

Moody College professor researches how to better understand speech in noisy environments

Catching up with friends while fighting for a spot at a packed bar or shouting over music at a concert can make holding a conversation next to impossible. Liberty Hamilton, an associate professor in Moody College of Communication’s Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, wants to know why.

Hamilton has frequently found herself in these situations — struggling to understand what her friends were saying over a cacophony of background noise and feeling even more lost when speaking Spanish over other chatter while studying abroad.

These experiences are what led her to want to study how we’re able to understand speech in noisy environments and how to focus on a single voice while drowning out distractions.

“I think that speech in noisy environments is one of those things that we intuitively know can be both really hard and really important,” Hamilton said. “The real world is noisy. There’s always something else going on.”

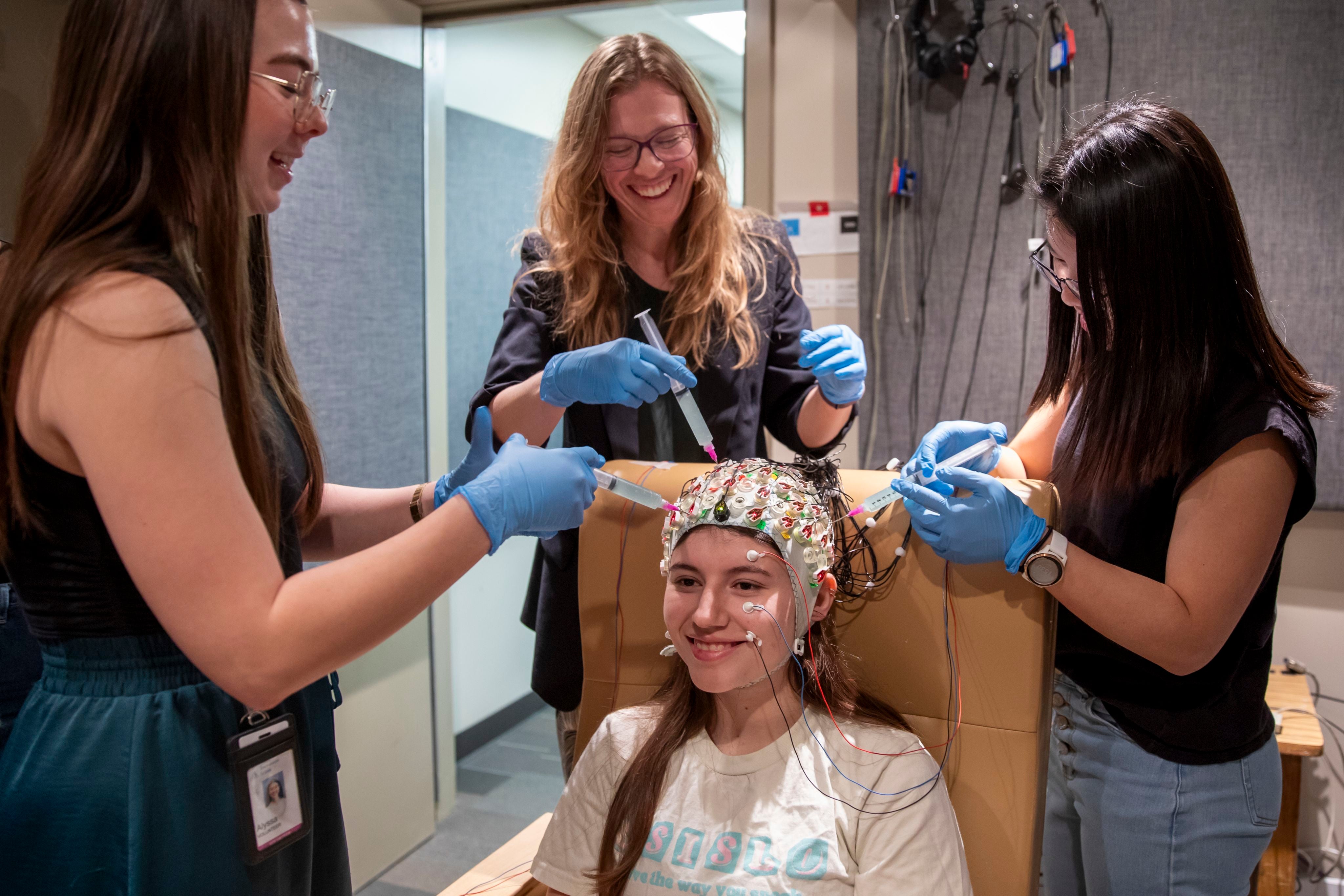

Hamilton starts small in her studies by examining speech in controlled environments. In the Hamilton Lab, she has study participants listen to sentences with background noise added while connected to scalp EEGs. Hamilton monitors their brain activity by measuring tiny changes in electrical activity on the surface of the subject’s head.

“We look for how people are able to understand speech or how they’re not able to and whether that’s reflected in the brain activity,” Hamilton said. “One of the things we want to find out is where the level of the auditory system is actually happening.”

People’s ability to understand speech can stem from an issue with their brains, something that can be studied further using the scalp EEGs. Hamilton has found that some struggle to understand speech in noisy environments because of problems in their ear or because of Auditory Processing Disorder (APD). APD is a disorder that causes a disruption in the way a person’s brain understands what they’re hearing.

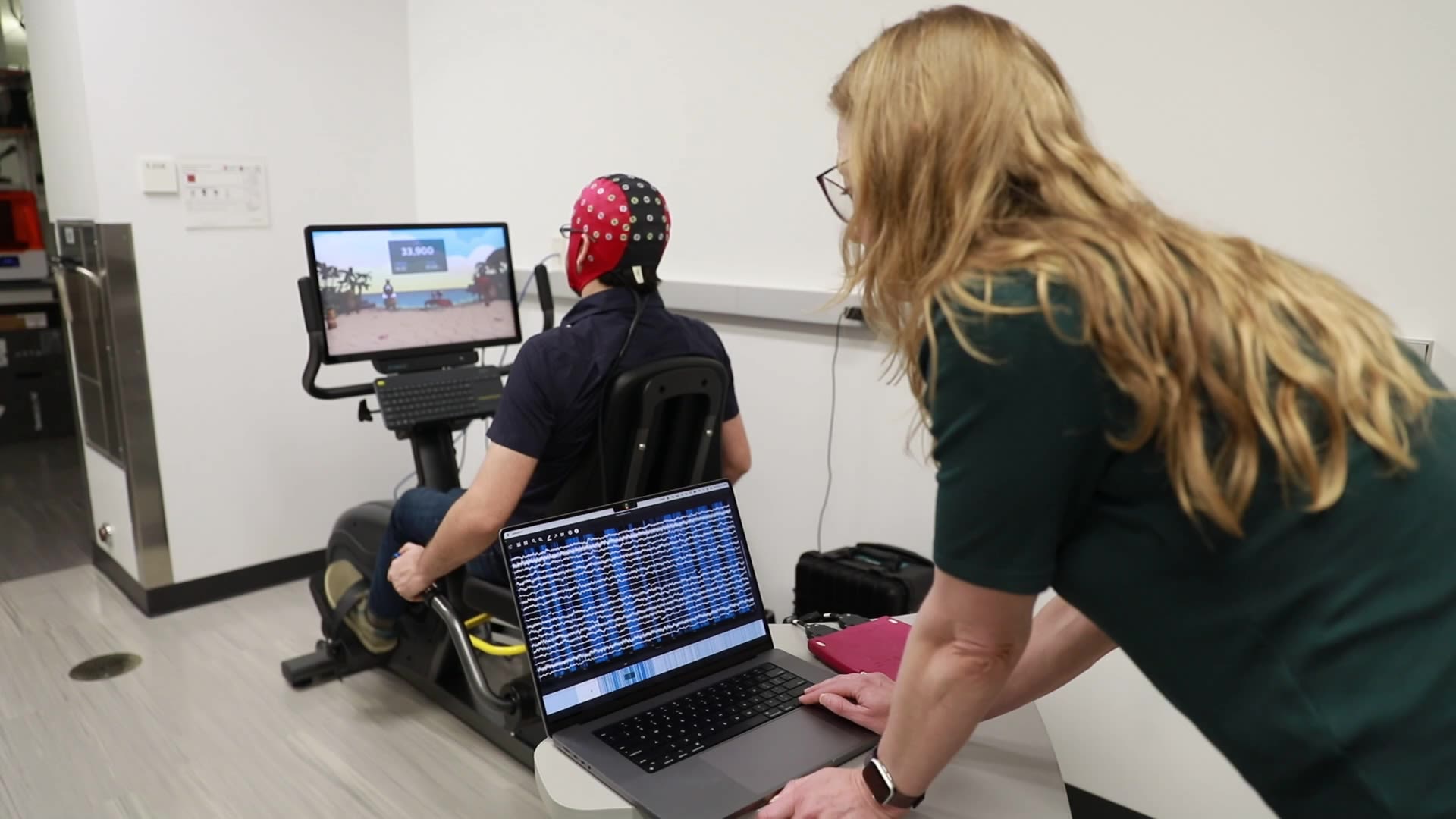

In another intervention, Hamilton and fellow researchers have participants ride a stationary bike while playing a video game. This tests whether the person can pay attention to speech coming from different areas while ignoring other noise. It has the dual purpose of trying to improve people’s auditory attention.

“There’s some evidence that exercise can help induce or enhance neuroplasticity,” Hamilton said.

Photos by Leticia Rincon

Photos by Leticia Rincon

“We look for how people are able to understand speech or how they’re not able to and whether that’s reflected in the brain activity. One of the things we want to find out is where the level of the auditory system is actually happening.”

Hamilton and her team’s work has led to a few key discoveries while also opening the door to other questions.

According to Hamilton’s research, very high frequencies of sound aren’t typically checked for during hearing tests but can be crucial to understanding how people decipher speech in crowded environments.

“No two people are the same, and even speech and noise can look different in different people,” she said. “In terms of if they’re having trouble, there can be different reasons for why. For some people, those high frequencies might actually be fine, and in the end, it could be an attention-related thing.”

Avoiding excessively noisy environments can be difficult in large cities like Austin, which are full of music and traffic. Wearing hearing protection can be one of the best ways to avoid having these problems. Custom earplugs that filter out noise and make important sounds clearer are becoming more readily available, and researchers at Moody College’s Speech and Hearing Clinic are working to improve these by carrying out studies like this.

Hamilton has high hopes for the future of her research. More innovative solutions are coming out every day, including the concept of cognitive hearing aids: devices that could allow wearers to selectively and exclusively amplify sounds they want to pay attention to.

“Part of this research that’s exciting to me is the collaboration between neuroscience, audiology, speech language and hearing science, and engineering,” Hamilton said. “I think by having all of these folks working together, we’re getting at some really interesting interdisciplinary questions.”