Real or Robot?

Real or Robot?

Virtual influencers are changing the game in advertising. But Moody researchers discover limitations.

Social media influencer and musician Lil Miquela cares deeply about social causes. She's a vocal supporter of LGBTQIA+ rights and the Black Lives Matter movement and reads self-help books to better herself. With her freckles and brown hair chopped with pixie bangs, she is objectively attractive. She has a boyfriend, spends time going out with friends and loves ice cream.

The catch: she’s not real.

Lil Miquela is not a person but a strikingly human-like computer-generated image. A self-proclaimed 19-year-old robot, she is one of a growing number of virtual influencers that are garnering a prolific following online and capturing the hearts of their digital audiences.

With almost 3 million Instagram followers and 200,0000 monthly listeners on Spotify, Lil Miquela was named one of the “most influential people on the internet” by TIME Magazine in 2018. Her influence has landed her a plethora of high-profile brand endorsements and modeling gigs for luxury designers like Prada and Burberry.

Created by software company Brud Inc. in 2016, she has a whole narrative and personality.

“She completely tells people she’s a robot,” said Matt Eastin, a professor in Moody College’s Stan Richards School of Advertising & Public Relations who studies virtual influencers. “She’s just living a mixed reality life.”

Virtual influencers are defined as “any digital character who has a first-person personality on social media,” according to Virtual Humans, a website by Offbeat, a digital media company. And they’re being used more and more because of the benefits they provide brands. They are completely controlled by the companies or individuals that run them, unlike human influencers. They can be curated with the personality, look and values that appeal to a specific audience, and they're less controversial since they won't get backlash for saying or doing the wrong thing on social media like human influencers do.

Moody College of Communication alumna Emily Berk, who worked for Offbeat after graduating in 2020, has both researched and created virtual influencers throughout her career in digital marketing and is well-versed in their behavior and effectiveness.

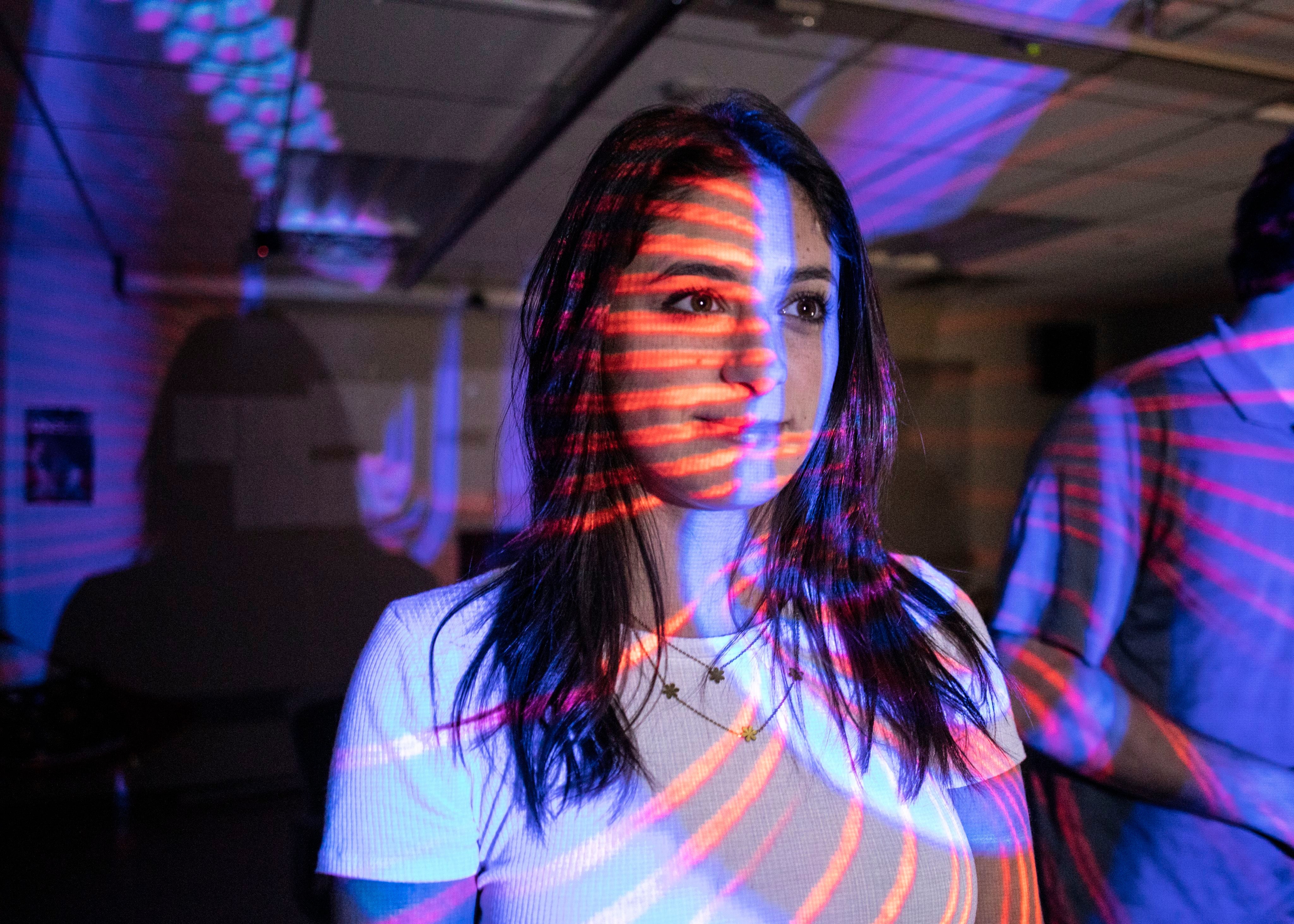

Virtual influencer Lil Miquela dining out. Photo credit: Instagram

Virtual influencer Lil Miquela dining out. Photo credit: Instagram

“I remember when I first got introduced to the virtual influencer industry about two years ago, the majority of the comments online were questioning, ‘Is this person real and what's this about?” Berk said. “We're seeing less and less of those comments now and more people just playing into the storyline.”

From CGI characters to illustrations, virtual influencers come in many different forms but behave similarly to humans, interacting with social media users, creating content and even promoting products or endorsing brands, Berk said. While these influencers are made using advanced and often expensive technology, they are designed and managed by humans.

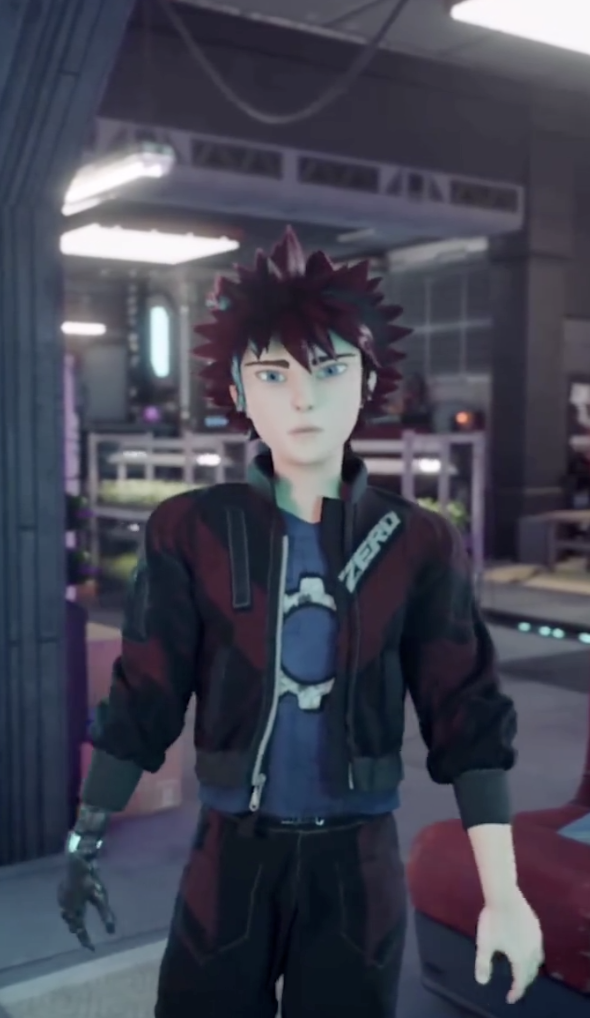

Corporations are employing virtual influencers to endorse their brands, such as the GEICO Gecko or the Barbie YouTube channel. Offbeat’s virtual influencer, Zero, posts dances on TikTok and streams on Twitch while playing video games. Celebrities have also been launching their own virtual influencers as well, Berk said.

Young people are most comfortable interacting with virtual influencers as they are already accustomed to playing as virtual characters in video games and using avatars on social media, Berk said. As social media users become more comfortable, she said virtual influencers will continue to become more prevalent in digital spaces.

“It’s really after people began to overcome that barrier of understanding that this is not actually a real living thing that the true fans started to come in and really support these virtual beings,” Berk said.

Virtual influencer Zero from Nexus. Photo credit: Instagram

Virtual influencer Zero from Nexus. Photo credit: Instagram

Moody College’s Stan Richards School of Advertising & Public Relations has been at the forefront of research into the virtual influencers space. Since 2020, Eastin and his students have conducted multiple studies about how various behaviors, settings and emotions affect how virtual influencers are being perceived by social media users. The studies focused on Lil Miquela, because of her prominence in the industry and human-like nature.

The team’s key question: How real is too real?

Eastin and fellow researchers have discovered some limitations for virtual influencers, and their findings could give digital marketers pause when using the technology.

In a recent study, Eastin, along with student researchers Jeongmin Ham and Sitan Li, looked at how Lil Miquela’s different human behaviors and social cues affect her perceived anthropomorphism, or realism.

A group of college study participants looked at posts of Lil Miquela holding ice cream, consuming ice cream and without ice cream versus whether she was alone or with another human. While perceived realism had a positive impression on study participants to a certain degree, being too human-like made Lil Miquela less favorable, Eastin said.

“We saw that there was a breaking point for the audience when she was with another human and consuming a real product,” Eastin said. “People go wait a minute, ‘That's too much.’”

This distinction is known as the “uncanny valley effect.” As virtual influencers reach an increasingly high level of similarity to humans, social media users reactions turn from delight to disgust. Cognitive dissonance plays a role as well, as people tend to have conflicting thoughts and actions about virtual beings.

“Too many assumptions that we have about robots and being human conflict, and you just sort of lose your audience,” Eastin.

In another study, Eastin, Ham and student researcher Pratik Shah looked at mixed reality settings where virtual influencers are placed alongside real places, products or people. The study used posts of Lil Miquela promoting either virtual products or real products alongside real humans or alone to see if a mixed reality setting impacted social media users’ attitudes toward Lil Miquela and their attachment to the brand she was promoting.

Mixed reality, which is a blend of the physical and digital world, allowed social media users to perceive Lil Miquela as more real, competent and warm, therefore resulting in positive attitudes toward her. However, when Lil Miquela was promoting a real product alongside a real person, attitudes declined.

Brand attachment was highest when Lil Miquela was promoting a virtual product, but that too decreased when she was with a human. Participants’ attachment to the brand was lowest when Lil Miquela was promoting both a real product and with a human.

“A lot of people might think because she's virtual, she might be best suited for the whole virtual space and virtual products,” said Ph.D. student and researcher Jeongmin Ham. The team’s study found otherwise, something brands should consider when employing virtual influencers.

In their most recent study, Eastin and his team looked at how social media users responded to different emotions expressed by Lil Miquela, including happiness, sadness, sexual desire and love. The study found that when virtual influencers express emotion, they are more likely to be perceived as emotionally intelligent. Lil Miquela was perceived as most emotionally intelligent when she was expressing happiness but the least when she was sad, the study found.

“Sadness actually brings everything down,” Eastin said. “It’s almost like in seeing her cry, we lost the audience for a little bit.”

Eastin expects that virtual influencers will be a commonly used tool for advertisers that will be most effective when integrated with mixed reality settings while avoiding the uncanny valley effect.

The brands who use them should take heed: there is such a thing as too real.

In the long run, Berk believes the use of virtual influencers could present concerns as artificial intelligence technology advances.

“As these virtuals can start truly working on their own, I think that's a time to be concerned,” Berk said. “For example, a purely AI virtual being that was modeled after a real living person could potentially establish a digital life that negatively affects that real person."

In the future, Ham said virtual influencers will likely move beyond social media into customer service, retail, entertainment and fashion industries. While much of the future about these beings remains uncertain, Eastin and Ham are confident these virtual beings will become increasingly prevalent, making it crucial to better understand them.

“We’re seeing a lot of movement going towards virtual space," Eastin said. “The more we can understand about it, the better we're going to be at designing these virtual beings and the better we'll be at interacting with them.”